“The stories told in Not a Hero are dedicated to my co-workers and everyone in active service, as well as former SEALs who have dedicated their lives to serving freedom. In our community, we constantly mentor the younger generation, share experiences and pass on the values that others have taught us, so that in turn the young can do the same for those who come after them. I hope this is what I was able to do for the readers of Not Hero.

- Mark Owen.

I was at home in Virginia Beach, waiting for the book to start.

It was August 2011 and the city was packed with tourists. Every day I drove past vacationers heading to the ocean to spend the day on the beach. I stayed away from the Oweshenfront, which runs parallel to the coast, which is the place where hiking jerseys are sold and minigolf courses attract sunburned vacationers. The tourists were completely absorbed in the beach mood, and I could not think of anything other than my upcoming business trip to Afghanistan.

The idle chatter of high officials and political leaders is finally over. Now the prospect will again go abroad did not let me go, as if the dog, ready to break out ahead, was not letting go of the leash. But first, I had to get through the wait.

Waiting is the worst that could be.

Everything went in a circle. We did weekly briefings on the latest information from every hot spot in the world that made it worse. We all wanted to work, to carry out real combat missions. But in anticipation, all we could do was plan missions that most likely never will.

On a business trip, it was in the order of things to get an assignment, jointly draw up a plan and complete it several hours later. But most of the surgeries we anticipated did not end up happening. We got involved in the work, planned the operation, only to get on our ass again, because in Washington another option was found, or everything calmed down in a hot spot. Even worse, we stayed at home, but there was almost no time for family. The family receded into the background, as we, as always, did not know when a sudden departure would take place. However, my family was always with me, in my thoughts, which always helped me on business trips. I went into standby mode.

I knew it was the same with my comrades. We all just wanted to get to work.

It was evening and I had just finished my supper. While we were on hold, there was no party or drinking. The last thing we would like to do is appear drunk for the upcoming mission. I assumed it would be a lazy evening in front of the TV until I got a few sms about the helicopter crash. All messages spoke only of this.

“A helicopter crashed in Afghanistan. Our?"

It was what we call "rumored intelligence" - a mixture of real news and rumors that often rolled into idle chatter. Unfortunately, this time it turned out to be true.

I only read one text message, and my mind began to scroll thoughts. If this is true, then it makes no difference who the SEALs were, Delta or Special Forces. All of them are my colleagues doing the same thing. I called a good friend of mine from the detachment on a business trip. He was not with his detachment, but at home, caring for his sick mother. I was hoping he knew something.

The phone didn't answer.

I continued flipping through the contacts on my phone, hoping to call at least someone who has information. Finally I got confirmation.

"It was our helicopter."

The news was like a shock. In my head, I began to remember all my friends in this unit. My phone was vibrating more and more as soon as the news spread. The messages were the same.

"It was our helicopter."

The stomach ached. I could not sit still. I walked around my kitchen with my head bowed and scrolled through text messages waiting for more information. I knew that my colleagues an infinite number of times voluntarily stayed in that place and did what they did. It could easily have happened that I could be in this very helicopter. Hell, I had a helicopter accident myself a few months ago. It was not easy at home either, waiting for at least a word, I knew well how most of our wives and girls feel.

I couldn't sit alone. I grabbed twelve packs of beer from the refrigerator and went to my friend "cat". We definitely could use a few cans of beer this evening.

The sun began to set and the streets were empty. There were a couple of blocks to my friend's house, I walked and examined the surroundings. The building in this place was new, there were almost no trees. Large brick houses and neatly trimmed lawns nearby. On weekends, I watched my neighbors take care of their lawn, trim the bushes to perfect condition. This view gave the street a serenity.

Most of my neighbors had no idea what I or any of the guys who come to my house do when they are at work. As I walked past the houses, I was sure that my neighbors were busy planning their vacations, paying bills or deciding and - what baseball game to watch this evening. It amazed me - what a gap between what is happening in Afghanistan and what is happening at home. I knew that my neighbors supported the military, but they can't even understand how often my colleagues risk their lives and how it feels. War is very different from everyday life at home, except for those families who are waiting for a sailor or soldier to go home.

The rest will never understand the sacrifice that our soldiers make every day. I couldn't change anything and it didn't really matter tonight. The sacrifice has been made. We can only remember about her. The gap between those who laid down their heads and the rest of the country has never been more visible to me than on that quiet evening.

When I got to my friend's house, he opened the door with the same sad face that I had. He nodded and motioned for me to enter. I quietly walked over to the refrigerator and put the beer there. I took two bottles and we went to the backyard, leaving his family in the living room.

I opened the beer and took a long sip. There was no taste. I needed an effect. A friend of mine was drinking and checking messages on his phone. We just sat there for a while. Neither of us dared to speak. The helicopter was jammed by our friends and they all died. It was a paralyzing feeling - we wanted to change something, but we couldn't help it.

The sun went down and darkness fell. I could barely make out my friend's face. He was in no hurry to turn on the light. I think we both felt more comfortable in the dark. The darkness made the grief a little easier.

For months, the SEAL teams were honored by politicians and the media following the killing of Osama bin Laden. I've forgotten how many times I've heard the word "hero". “Hero” is not a word that we pronounce with such ease and, in the end, it got to the point where it lost any meaning. Now everyone was a hero.

The extent of the loss didn't feel so much until the names started popping up on my iPhone.

The beer went on one by one, while we remembered the stories about the guys who were in the helicopter. We both tried to remember the best stories, funny stories, about each of them. There was no shortage of these stories. Humor has always helped us get through the toughest and most intense moments. We plunged into our memories and clung to anything that could cause laughter. My buddy went inside to get a couple more bottles when the new name appeared on the phone screen.

Ray.

It was like a blow in the stomach. I put the phone on the table and began to pace up and down. I met Ray for the first time in 1999 on the San Diego coast. We were both preparing to start BUD / S, the SEAL qualifying course. He was from Louisiana College. After studying for a year, he decided to become a SEAL. I made the exact same decision during my college years. I remember standing next to Ray, we looked at the surf and listened to the instructors yelling at us. He looked focused and confident. The noise and confusion surrounding him were completely indifferent to him.

Ray might seem like a quiet guy until you get to know him. Unlike me, he was a real athlete. He played football at school and had a lean physique. I often noticed that Ray did all the physical exercises so easily that it infuriated the instructors. In turn, this only made him stronger. He always followed through on what we did - swimming, running on the beach, obstacle course, whatever the conditions.

Together we finished BUD / S in December 1999. Ray was assigned to SEAL Team Three. I was also enrolled in SEAL Team Five. While we were based in San Diego we saw each other as often as we could. However, with our schedule, we usually were in different parts of the planet.

Ray, like a cat, had 9 lives.

Some of the cases when he was close to death became legendary. Ray was shot in the neck several months before the selection and training course or S&T. He was on a six month business trip to Guam with the SEAL Team Three guys. He and a few friends went to a bar to celebrate Christmas. After a little squabble with the locals, Ray and his SEAL buddies decided to leave. They got into a taxi and were already about to go towards the base, when suddenly one guy from the bar leaned out of the window of the car next to him and opened fire.

Bullets hit the taxi windows. One of them hit Ray in the neck and went right through. Larry, another SEAL fighter, was shot in the ear. As a result, the bullet came out of the nose. The taxi driver quickly drove both to the hospital. Ray covered his shirt with blood and went to the operating room on his own for treatment.

A few months later, he showed up for the qualifying course (S&T). He was in my class and we passed it together, but as soon as BUD / S was over, we were assigned to different squads.

Ray was now dead. And I still couldn't believe it.

My buddy brought in more beer, thus ripping me out of my dark thoughts. We sat again for a while in silence. We both had phones in our hands, we were waiting for new messages. But I kept thinking about Ray.

“Hey,” I said. "Have you ever seen that video of Ray in Afghanistan?"

My buddy laughed out loud.

“If I had been in his place then, I would have been dead,” he said.

Often in the morning, when we got to work and checked our mail, there was an After Action Review (AAR) waiting for us. In fact, this is a report, sometimes it contains a video from a drone observing all participants in the mission. Everyone - from helicopter pilots to intelligence analysts to SEALs themselves - discusses everything that went right or wrong during the mission. These reviews (AARs) were distributed so that whether you took part in the mission or not, you can always draw conclusions from the actions of the unit that participated in the operation. And this often caused a storm of discussions among us, especially after interesting missions.

Ray's mission was what is called "it was necessary to see." Ray's squad was in Afghanistan. His detachment stormed several houses behind which there was a clay wall. Ray was then one of the snipers and climbed to the roof of the building next door, began to monitor the place where the Taliban commander was hiding, and provided cover for the assault.

Watching the video, I watched the assault squad quietly move towards the desired building. I've done the same thing a million times, so I knew how these guys felt back then. I was in awe of just watching them. I knew that now their senses were heightened, they were listening to all sounds, whether it was the door opening or the noise of pebbles under the Taliban shoes. I caught myself thinking that I myself was examining the buildings with my eyes in search of any movement.

As soon as Ray started to cover the guys, he watched his every move. I am sure every creak of the thin clay roof made him freeze, he knew that any wrong movement could give his position to people sleeping in this building.

As the assault party approached their target, the door directly below Ray's position opened from the inside. The familiar silhouette of an RPG appeared from the opening - a thin pipe with a shot at the end. Then a short pause - a few seconds. I assumed that someone in the building under Ray's position still heard him or those who were storming. The Talib were most likely trying to make out the approaching SEALs in the darkness. A second later, a rocket flew out, passed right in front of the squad and exploded somewhere off to the side.

The blast was enough to crack the clay on the roof of Ray's building. Its middle cracked, engulfing Ray like a huge mouth, and he fell somewhere in the center of the house.

Ray landed on a pile of rotten logs and clay. Through a cloud of dust, he noticed five Taliban with AK-47s and unloading with magazines in them. Some of the Taliban were lying on the floor, knocked down by the blast of RPGs.

Ray had only a few seconds to make a decision: to stay and open fire on five Taliban, or to dump from the house until his fellow SEALs, who did not see that he fell inside the house, opened fire on the building.

Ray decided to get out of the house.

He quickly jumped out of the nearest window. In the video, I saw Ray collapse to the foundation. Ray started shouting to identify himself to his guys. He hoped that he would not be mistaken for one of the Taliban.

Further in the video, it was seen how Ray crawled away and calmly pulled out a grenade. Then he got to the edge of the window and threw a grenade inside the house. In the video, Ray looked cool. All his movements were calm and calculated. It seemed that this insane situation was routine for him.

Ray again crawled away from the window in search of some cover. A grenade in the house exploded and a cloud of debris and dust flew out through the hole in the roof. Inside, everyone was killed.

Ray, like many of us, has served his country for over ten years. His actions and actions reinforced the principles by which we lived as a team and I knew that Ray was working at the peak of his abilities, which made us more united and helped save more than one life.

While my friend and I were sitting, I thought how nice it would be to sit with Ray like this. For the rest of the evening we talked about our lost brothers and tried to remember what we could have forgotten. It made no difference to me how they died. The bottom line is that all of them cannot be returned.

A few days later, details of this disaster began to arrive. It was important to understand and draw conclusions from what happened. The casualties were part of the Rapid Reaction Force (RRF) that night. The RBU is on duty and ready to act instantly if things go wrong somewhere.

The Rangers went on a mission to the village of Jaw-e-Mekh Zareen, Wardak province, Tangi Valley. At first, they wanted to send SEALs on a mission, but they refused, since the moon was shining brightly that night and the unit decided it would be safer to wait until dark. When the SEALs abandoned the mission, the Rangers decided that they would take the mission for themselves.

The assignment was one of the important Taliban commanders. The fight began as soon as the Rangers landed. The Taliban attacked from both sides of the valley and defended the road to the development. The battle lasted two hours until the Taliban began to retreat. The Rangers called in the RBU for help. They feared that the same commander with his bodyguards was among the retreating ones, the Rangers did not want to let him go.

Helicopter - callsign Extortion 17 - already flew up to the Rangers when an RPG from the Taliban hit him in the main rotor. Ray and the guys never got a chance.

Two days later, the command in Afghanistan announced that the Taliban, who shot down the helicopter, had been destroyed by an F-16 raid.

It didn't make it any easier.

Later rumors began to spread and go in circles. It was rumored that the Taliban had lured SEALs and shot down a helicopter in revenge for the murder of Osama bin Laden. Be that as it may, the truth is one - the Extortion 17 disaster was a tragedy. When an RRF is called in, something often goes wrong. It is dangerous to be in the SBR. The element of surprise is missing, especially when you arrive in the Chinook, which is essentially a flying school bus. Sometimes skill or luck isn't enough - it's just your time.

As new information arrived that evening, I was learning that many of my comrades had lost their lives in Afghanistan. Thirty-eight military personnel were killed when the RPG struck Extortion 17. More than a dozen were SEALs. This plane crash was the deadliest in the entire war in Afghanistan. The flags on the coffins during the funeral procession are forever ingrained in my memory.

Of course, Ray isn't the only friend I've lost in my fourteen years with SEAL. There are forty names in my phone contacts that I will never call again. Many more SEAL guys died after 9/11, but these forty people were the ones I was lucky to know and serve.

Together we will never again remember the glorious days of our business trips with beer. No picnics or training outings. All forty were more than colleagues or friends. They are brothers. Every time I glance over their names in my notebook, they come to life in my memory.

We all arrived in San Diego with the same dream. This is what connected the Alaska hinterland boy and put him in line with the California surfer and the Midwest farmer who saw the ocean for the first time in training.

I pursued this dream from school in Alaska to BUD / S. Once I got my trident, the special SEALs badge that they wear on their uniforms, I tried to be the best on any assignment. For me and many of my colleagues, becoming a SEAL is just the start of our big dream. It has become our religion to be a great companion who is constantly improving and to be close to your colleagues in any situation.

I will never accept losses. This is the biggest blow to me in my entire service. My colleagues sacrificed everything for their country. They spent months away from their families, freezing in the cold mountains of Afghanistan, and some, like Ray, paid the highest price. None of them considered themselves a hero.

I had to make a decision.

For fourteen years I tried to be one of the best SEALs. I was able to. Now I either stay in the Navy long enough to earn a pension, that's another six years, or I quit and look for a new challenge.

The decision was weighing heavily on my soul, such as I had never felt in my life. Being a SEAL - being one of the best teams in the country was more than just a job for me. This was my whole essence and the most important path in my life. I knew if I left the service, the train would carry me so far that my whole life would change forever.

As I struggled to make a decision, I spent the evening taking stock of my career and the experiences I had that made me who I am. I decided to leave the navy and start a new journey.

The publication of the book pushed me into a new world, which I have never been, in this world there were a million strangers who suddenly wanted to communicate with me and listen to what I have to say to them. Most of the people I met were friendly and supportive, but there was also criticism. It was a new challenge, but the only thing I was sure of was that my training at SEAL had prepared me for that too.

I had been on thirteen missions and had been an operative for thirteen years when I left the Navy. My departure was difficult, I went to a new world where I myself did not know whether my skills would be needed or not.

When people heard about SEALs, they assumed we were superheroes who jump from planes and shoot bad guys. We did these things, but these skills did not give us a precise definition. When we made mistakes, we tried again and again and again until we could fix them. We are not superheroes. We are simply dedicated to our work.

There is no magic wand, but there is a lot of motivation, dedication and hard work.

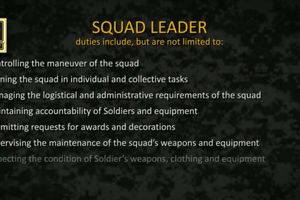

The reality is SEALs don't see themselves as special. We just put in the effort to do many things and complete assignments at the highest level. One of the best commanders I knew, during the selection of "young" people to test their readiness to become part of the team, asked them:

"At what level are you ready to take part in our business?"

Anytime, anytime, was the only acceptable answer.

We gained experience, often the hard way, of how to be the best. Being the best meant being in touch with each other, challenging, leading, learning and teaching day by day, him, year after year. This means not only being able to walk sixty pounds through the mountains of Afghanistan for miles, but being ready to answer for your mistakes. Answering to your mates, which is often more difficult than spending several hours in the cold surf.

As soon as I faced the first tests during the first year after leaving the Navy, I often returned to the lessons I learned from my service at SEAL and the people I knew and who will be with me my whole life. I realized that the most important moments were not the moments when I returned home. These were the moments when my squad and I were carrying out non-publicized missions, in which we received certain experience and from this we became better. These are the mistakes that I made, drew conclusions from them, and will not repeat them next time. The most important thing is what the SEAL Brotherhood was in essence.

This is a book about these moments that made me who I am now.

I hope that these stories, put together, will immerse you in the life and work of SEAL, show the experience passed down to me by my comrades with whom I served and those who served before me.

Being a SEAL isn't just a job. This is a life test of yourself and your comrades, a state of constant development, a test of your decisions and lessons learned from your own mistakes so that your squad can be as effective as possible.

Lessons learned during my service are the legacy of people like Ray - those who died and others in active service or ex-SEALs who dedicated their lives to their country. Many lessons were hard through the loss of friends. This book is dedicated to my brothers.

SEALs mentor the younger generation and pass on their experience to newcomers. I wrote "Not a Hero" because that's what I wanted to do.

Next Section: Chapter 1: "The Right to Wear the T-shirt. Purpose"