I slid my rifle behind me and started to climb up the metal ladder. I could hear it scrape against the side of the building as I reached for the next rung.

Ahead of me, my teammate had already reached the roof and slid over the small parapet wall. I reached the roof seconds later and climbed over, dragging more than sixty pounds of body armor and gear with me. Below, I could see my teammates slowly moving into position at the front door of the target.

We were the “roof team,” which meant we provided overwatch from the high ground. We were about to hit an insurgent safe house, and it was my team’s job to get to the roof to cover the assault. If we were able to enter the building from the roof, we assaulted down the stairs while the ground element assaulted up the stairs. Theoretically, we would capture the bad guys in the middle and hopefully before they had time to resist.

It was 2006 and Iraq was the big priority. The Army unit assigned had taken some heavy casualties and needed replacements. I was only about a month into my first deployment with my own unit when my six-man team was sent from Afghanistan over to Iraq to help. At first, we thought our entire team would be attached as a unit, but when we arrived we got separated and sent individually to different teams.

We flew into the military side of Baghdad International Airport and drove to the Green Zone, a walled-off area of the Iraqi capital occupied by Coalition forces. I’d been to Iraq with SEAL Team Five, so everything looked familiar. Toward the end of that deployment, I’d operated in Baghdad. At that time, we were all new, with little to no combat experience. But landing in Baghdad this time, it felt different. There was energy in the air, a confidence that pervaded the entire military because of our collective combat experience.

I was still pretty new to my team, and I’d never worked with the Army but had heard rumblings about how the two services did not get along. There was always this competition between the two, probably driven by our shared quest to be the best. There were shooting competitions and other drills that always seemed to pit the two units against each other. In my mind, I expected to see or experience this tension, but it never came. All the old-school drama over which unit was better had faded since the war started. We were one team. The team opened up, pulled me in, and made me one of their own. No one cared about which unit shot better when we were all working together fighting a common enemy.

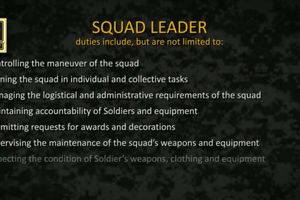

When I landed, Jon, my new team leader, met me at the operations center and took me to my room. He also showed me the chow hall and gym and introduced me to my other teammates. My new team seemed to be made up of guys very much like the SEALs on my old team. We used all the same gear, tactics, and command structure. They were Army, and I was Navy, and there were some cultural differences, but the basic makeup of the guys was very familiar.

Jon welcomed me and included me in all the planning. There was never a moment when I didn’t feel like I was part of the team, but more importantly I felt like Jon and the others were open to hearing my opinion.

Once, we were planning a mission a few weeks after I arrived. My team was slated to land on the roof of the target on an MH-6 Little Bird and clear down from the roof. Jon was working on the manifest, the list of guys going on the mission.

“Space is tight on this one, boys,” Jon said.

He was crunching the numbers to make sure we stayed under the weight limit. I was sure I’d be cut from the mission. I was the new guy and the SEAL. The planning was over and the rest of my team left the operations center. I got my notebook and headed back to the room.

“Hey,” Jon said as I started to leave. “You’re on tonight.”

Later, I saw Jon talking to the other new guy on the team. He was staying behind. The next time we exceeded the weight limit, I stayed behind. Jon always made it a point to swap me out with his other new guy, ensuring I got as much love as the rest of his team. Yes, I was still considered a new guy both at my unit and the Army team, but it was nice to know that Jon thought of me as part of his team.

After the first few missions, I folded myself into the team, and soon I was no longer looked at as the token SEAL replacement. I was just a teammate, one of two new guys on the team.

I’d just met these guys, but I already trusted them with my life and they did the same. I knew that they would risk their lives to save mine and I’d do the same for them. I credit Jon with making the transition seamless. He was one of the best leaders I’ve ever worked for in the military. He didn’t have the respect of his team and others just because he was the boss. He earned everyone’s respect because of his character, his leadership, and his calm demeanor in combat. It seemed like nothing fazed him. I immediately looked up to him as someone I wanted to emulate.

I realized over the course of my career that every special operations unit shared a common mind-set. We were all wired the same way. We all started with a shared sense of purpose. In the past, and in peacetime, there was a rivalry between the units. But once the shooting started, that rivalry was discarded in favor of teamwork, because if there was one thing we all agreed on, it was completing our mission and coming home safe.

If you think of a special operations team—SEALs, Special Forces, Rangers, and the Air Force Pararescuemen and combat controllers—like a boat, everybody rows. The officers down to the newest guy are trained to care about the team first and do what it takes to accomplish the mission. I saw the same mentality when I worked with the international special operations units.

Every single unit I’ve ever worked or trained with had that in common. Some of the gear and tactics might be a bit different. Some of the units had better toys, but in the end it didn’t matter if you had the most expensive rifle or had special training. We all volunteered for the hardest training we could find in our respective countries. We all learned to push ourselves to go well beyond our mental and physical limits.

Units like SEALs and other special operations units have been in existence since war was created. The Greeks had special units and George Washington’s army used sharpshooters during the American Revolution.

But only after World War II did officials start figuring out how best to screen and train special operations forces. And the first step was always finding guys with the right mind-set to achieve the group’s common goal. Mind-set is the common denominator.

Charlie Beckwith, after arriving in Vietnam in 1965, was given command of Project Delta—Detachment B-52. The reconnaissance unit was created to collect intelligence along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and in South Vietnam. Beckwith fired most of the soldiers in the unit when he took command and started to recruit replacements using a flyer.

WANTED: Volunteers for project Delta. Will guarantee you a medal, a body bag, or both. Requirements: have to be a volunteer. Had to be in country for at least six months. Had to have a CIB (Combat Infantry Badge). Had to be at least the rank of Sergeant—otherwise don’t even come and talk to me.

He wanted to find guys like my teammates, who possessed a never-quit attitude and a single-minded drive to accomplish the mission. Starting with the mentality from the flyer, Beckwith later created <CENSORED> based on what he learned from the British SAS.

But the military is not the only example. Ernest Shackleton, who led three British expeditions to the Antarctic in the 1900s, reportedly placed an ad in a London newspaper looking for the same type of man:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in event of success.

I would have signed up for Beckwith’s Project Delta and Shackleton’s expedition.

I never wanted to do anything normal. I can’t be average. No one involved in special operations can be average because our missions are never easy or routine. Both Shackleton and Beckwith were looking for a shared sense of purpose and a common mind-set among all their people. If anybody on their crews wasn’t there for the right reasons and for the team’s needs, there was a higher chance of failure. And failure in the special operations community is never tolerated.

Most nights in Iraq, I was perched on the landing skid of a Little Bird—an MH-6 helicopter flown by the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment—racing over the rooftops. I’d fast rope to the roof of a building and clear the top floors while my teammates in the trucks on the street cleared the lower levels. The missions were exactly what I signed up to do, but I was doing them with the Army instead of my SEAL teammates. We were waging a massive campaign to dismantle al Qaeda in Iraq.

We called it “Baghdad SWAT.”

But some nights, we didn’t have the Little Birds. If we were going to the roof, we had to climb.

As I crested the parapet wall, I looked back over my shoulder and saw that Jon had reached the roof. I turned and headed for the opposite corner, scanning for any targets. Tile covered the roof and a small two-foot-high parapet wall ran completely around the edge. A door sat in the middle of the roof and a myriad of satellite dishes of all makes and models were attached to the corners of the building. Bundles of thick black power lines ran from building to building, sagging over the road and alleyway.

I had a map of the area in my head and knew the target we were looking for was on the other side of the roof. Over the radio, I heard the ground team searching for the correct door. The enemy safe house was in a duplex, but from the radio traffic the ground team was unsure which door to breach and enter.

From my perch three stories up, I could see the ground team’s trucks. I heard a muffled boom, and the Army operators on the ground started to move into the house. I kept watch on the house, waiting for any sign of movement.

Then word came over the radio. The boys hit the wrong side of the duplex. They were going into the other side of the duplex now. I heard a burst from an AK-47 and some yelling.

“We’ve got squirters,” I heard over the radio.

From our vantage point, I knew that the squirters had to be close, but they were out of sight. We couldn’t see into the alley located to the north of our location because of the building in front of us. We needed to cross over to the other building, but there was no time to go all the way down to the ground floor, move over to the next building, and then clear our way back up three floors to the roof of the other building.

Nearby on the roof, I noticed a ladder. It looked long enough to reach the parapet wall on the other building. From that roof, we’d have a perfect angle down on the alley the enemy fighters were using to escape.

I looked at Jon, but he was working the radio, which was jammed with reports of fighters on the run. The guys inside the building also found a cache of weapons and explosives.

I wanted to get into the action, so I ran over to the ladder. It was made of discarded pieces of wood nailed together. A single nail and some wire held some of the ladder’s rungs on. I grabbed the ladder and put it on my shoulder and ran over to the edge of the building where my teammate waited.

“Think this haji ladder will hold us?” my teammate asked.

We were three stories up. I stood on the lip of the parapet wall and looked across the open space between the buildings. It was about fifteen feet across.

“If we lay it flat and crawl across, I think it will,” I said, hoping more than believing it.

“Either way, we’re about to find out,” he said with a smirk.

We both wanted to get in the fight and stop the squirters from escaping, or worse, setting up an ambush. We gently slid the ladder across the alley. My teammate went first. Lying flat, he slid across the ladder while I held it and kept watch on the other building. When it was my turn, I slung my rifle around behind me so it rested on my back and started to crawl across.

My mind went back to thin ice in Alaska. The only way to get across thin ice is to spread your body weight out as wide as possible. If you stand up, all your body weight is in one spot, and the next thing you know you fall through into freezing-cold water. Like crossing thin ice, crawling across the ladder was very dangerous. We were three stories off the ground, enemy fighters were running around, and we were about to trust this piece-of-shit Iraqi ladder to keep us from falling.

At least in Alaska I hadn’t been wearing the additional sixty pounds of gear.

I took two deep breaths and tried to stay focused. This was one of the many times staying in my three-foot world kept me going, because I still hated heights.

Inch by inch I crawled across the alley. Below, I saw a massive pile of trash. Most of it looked like kitchen waste, with rotting food and various food containers. Plastic bags were blown around the alley, and it looked like a car or truck had hit the waste pile, scattering trash into the middle of the alley.

I never stopped moving and finally made it to the other building. Back on my feet, I raced over to the corner, looking for the squirters. The enemy fighters would have easily gotten away had we hesitated or decided not to use the ladder. I picked up the squirters running at a dead sprint just as we got to the edge of the building and looked into the alley. Both men were carrying rifles.

I could see my teammate’s laser stop on the fighter on the left. I zeroed in on the fighter on the right. We both opened fire and cut the fighters down before they could get to the mouth of the alley. They had gotten lucky when the ground force hit the wrong side of the duplex, but that’s where their luck ran out.

On the other building, Jon heard the shots. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him hustling over to where we’d left the ladder. I turned back to the alley and kept scanning. My teammates in the house were still clearing rooms and finding weapons, but it was unclear how many fighters were in the safe house.

Above me, I heard AH-6 Little Birds crisscrossing in the sky. They were armed with rockets and machine guns, ready to engage if we ran into trouble. After the first reports of squirters, they started flying in ever-widening circles from the target, looking for fighters who might have escaped.

Then I heard an urgent call over the radio.

“We’ve got a man down,” the Little Bird pilot said.

A few seconds later, the pilot repeated the call.

“We’ve got a man down.”

At first I assumed that the ground force had taken a casualty as they finished clearing the target building. Then the pilot came back with a second report.

“We’ve got a man down roughly one hundred meters south of the target compound,” the pilot said.

That didn’t make sense. I was located one hundred meters from the target with Jon and my team. We’d made contact, but the pilot couldn’t be talking about us. We were fine. The fighters never got off a round.

I glanced over at my teammate. He shrugged. I turned back to see if Jon was on our roof so I could ask him about the radio call.

Jon was gone.

“Where did Jon go?” I asked my teammate. “He was just there talking on the radio.”

“Where’s the ladder?” my teammate said.

Shit.

We both sprinted over to the edge of the building. The ladder was gone. I looked over the side and saw Jon lying in the pile of garbage. His helmet was turned to one side and I could just hear a faint moan as he rocked in pain.

“Roger, I’ve got a visual,” I said over the radio. “He is in the alley between the buildings located just south of the target.”

The helicopter saw him go down and must have called it in to the guys on the ground. Now the medics wanted to know how to get to him.

“Get on the GRG and let’s talk some people in to get him,” my teammate said. “We need to get down there now.”

We were still getting reports of additional fighters in the area. If they stumbled upon Jon, he was dead. I pulled out my GRG—a gridded reference graphic, which is a small map with the buildings in the area identified by number—and started to guide the guys on the ground to Jon.

GRGs are usually made of satellite photos of the area, and they are often used to call in air strikes by providing the pilots and the guys on the ground with the same point of view.

“Stand by,” I said into the radio. “He is down in the alley at the intersection of Echo Four and Delta Eight.”

The ground force immediately sent their medical team to the location using the coordinates off the GRG. We stood on the roof and covered him until our teammates entered the alley. Then we started to look for a way off the roof. We couldn’t go back to the original building because the ladder was lying in the alley in two pieces. The roof of the new building was identical to the roof of the first, with a door leading downstairs. It was unlocked.

I tried to focus and calm myself down. I was really worried about Jon. Over the months that I’d worked with Jon, he’d become a mentor and a friend. I felt like he and my other teammates were brothers, much like my fellow SEALs. I would hate for anything to happen to him. From my perch on the roof he didn’t look so good, but I could hear him moaning and with my medical training I knew that this was at least a good sign.

“Let’s go,” I heard my teammate whisper as he motioned toward the door that led down into the building.

I slowly moved down the staircase with my rifle raised and ready to fire. It was always a little shocking to enter buildings in Baghdad. From the outside, it was hard to tell what they looked like inside. Many times, we hit houses that looked run-down, only to find nice furniture and fixtures in the rooms.

I had no idea we were on a house when I shimmied across the ladder a few minutes earlier. The stairwell opened into a hallway on the third floor of someone’s home. My boots squeaked on the marble floor as we started toward a staircase at the end of the hall. I took a cursory glance in each room as we passed. I wanted to make sure no fighters were there, but that was it. We weren’t really clearing the entire house. We needed to make our way to the exit and to Jon.

We came down the marble stairs leading from the third floor to the second floor. The staircase kept going down to the bottom floor. We were on our way down to the second floor when I saw a man standing on the landing just below. He was dressed in a dishdasha, the long robe worn by Arab men, and sandals. His arms were out and half raised like he was making sure I saw he wasn’t armed.

“Can I help you?” he said in English and with only a slight accent.

I was about to start yelling at him to get down on the ground, but the near-perfect English startled me.

“We need to get downstairs,” I said.

“Follow me,” he said.

I got close to him and kept my rifle trained on his back as he led us down to the second floor. I didn’t trust him, but I also thought it was unlikely he had fighters in the house. I got the sense he just wanted to make sure we didn’t smash up his house trying to find a way out.

“I’m a professor,” he said.

I didn’t answer. I didn’t really care. I just wanted to get out of the house and get to Jon’s location. My mission started as a hit, but as soon as Jon got injured, the mission changed.

The professor led us down to the front door and undid the locks. He opened the door and stepped out of our way. My teammate told the professor to move away from the door and stay quiet. I stopped at the threshold and peered out, looking for any fighters. Confident we were safe, I led the way out of the door and into the alley.

In the alleyway, I could see a medic kneeling next to Jon. He was wide-awake and still moaning. He’d fallen three stories down into the alley and landed in the pile of trash. It was likely the only time a pile of Iraqi garbage saved anyone. Most of the time I worried about bombs planted in the piles that lined the streets and alleys of the Iraqi capital.

When we got there, the medic was talking to Jon.

“Can you stand up?” the medic asked him.

“Yeah,” he said.

Jon didn’t have any broken bones. He let out a long groan as we helped him up and walked him over to the waiting trucks. He slumped down into the back of the truck and let out a deep breath. He was hurting but didn’t want to show it.

“Dammit. That sucked. The fucking ladder broke,” Jon said.

Jon didn’t see us set up the Iraqi ladder, and in the moment, hustling to get to our position after he heard us fire shots, he thought it was one of our metal ladders that we carried on every target. All he had on his mind was getting to us to support in any way that he could.

He decided to walk across instead of crawling over the rungs on his stomach and spreading out the weight like we had done. He tried to walk rung by rung across the ladder, which had been lashed together with old wire and rusty nails. He was three stories in the air, wearing more than sixty pounds of gear, and looking through night vision goggles. Even our goggles, which were some of the best, made depth perception difficult.

The feat would have been hard during the day, and even on a metal ladder, but Jon attempted to do it at night, in combat. He made it halfway and probably would have cleared the entire distance without falling had the ladder not snapped in the center under his weight.

I was stunned listening to him tell us what happened. It took balls to walk across a ladder, at night, during a firefight. I started to kid him that the ladder broke from the weight of his testicles.

We wrapped up the raid soon after and drove back to the palace. Jon moaned each time the truck hit a rut in the road, and in Iraq all of the roads have ruts. When we got back, he didn’t go to the hospital. He sat through the AAR before going to bed. Jon took two days off and then returned to full duty. He’d suffered some bruises, but no serious injuries.

I was relieved to see him two days later on the skid of a Little Bird flying to a new target, but not as relieved as he was. There was no doubt missing a mission and knowing we were going into harm’s way without him was worse than any pain from his fall.

I still keep in touch with Jon to this day. In fact, I went to his retirement party last year. It was an intimate affair with only those close to him. Jon still had the thick chest, but no beard. Like me, he looked older. Not from the years, but from the mileage. He gave more than twenty years of service to his country.

Jon calls me his “favorite SEAL.” It is a distinction I take great pride in, since not only was he one of the best leaders that I ever worked for in my entire time in the SEALs, but he has also become a lifelong friend. Even after I returned from that deployment in Iraq, and despite our busy schedules, we managed to keep in touch. The conversations were more than just catching up on current events; we’d always compare the latest tactics and techniques used by our respective units. The competition between Army and Navy had officially ended in our minds, and we were one big team that always had each other’s backs. Jon was my swim buddy on the “green” side.

I’d arrived in Baghdad a nervous new guy who wasn’t sure I’d click with the Army guys. But I’d learned almost from day one that we had the same mind-set. We shared a common purpose, and that allowed me to become a member of the team. We didn’t get caught up in meaningless rivalry based on the color of our uniform. We may use different equipment and have our own selection courses, but we are all the same in our minds.

We all volunteered to go on the most dangerous missions, where, as Beckwith put it, “a medal, a body bag, or both” are common. We can all accept “low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness” like Shackleton promised, because we’d all rather die than fail.

But most of all, we always put the team over the individual and never accept anything but the best from everyone. Those words are easy to say and write, but hard to live by. But those are the kinds of men I served with in the special operations community, men who share a common sense of purpose and a nearly identical mind-set.